Honoring Your Context

The genogram is a kind of family tree that not only provides important names and dates, but also denotes patterns of relationship, mental health, and more. For certain personalities, it’s a very appealing way to begin the psychotherapy process. At minimum, a genogram represents three generations of one family. Some clients, though, can provide information that goes even farther back in time, which is ideal. More chronological depth means an opportunity to recognize more patterns.

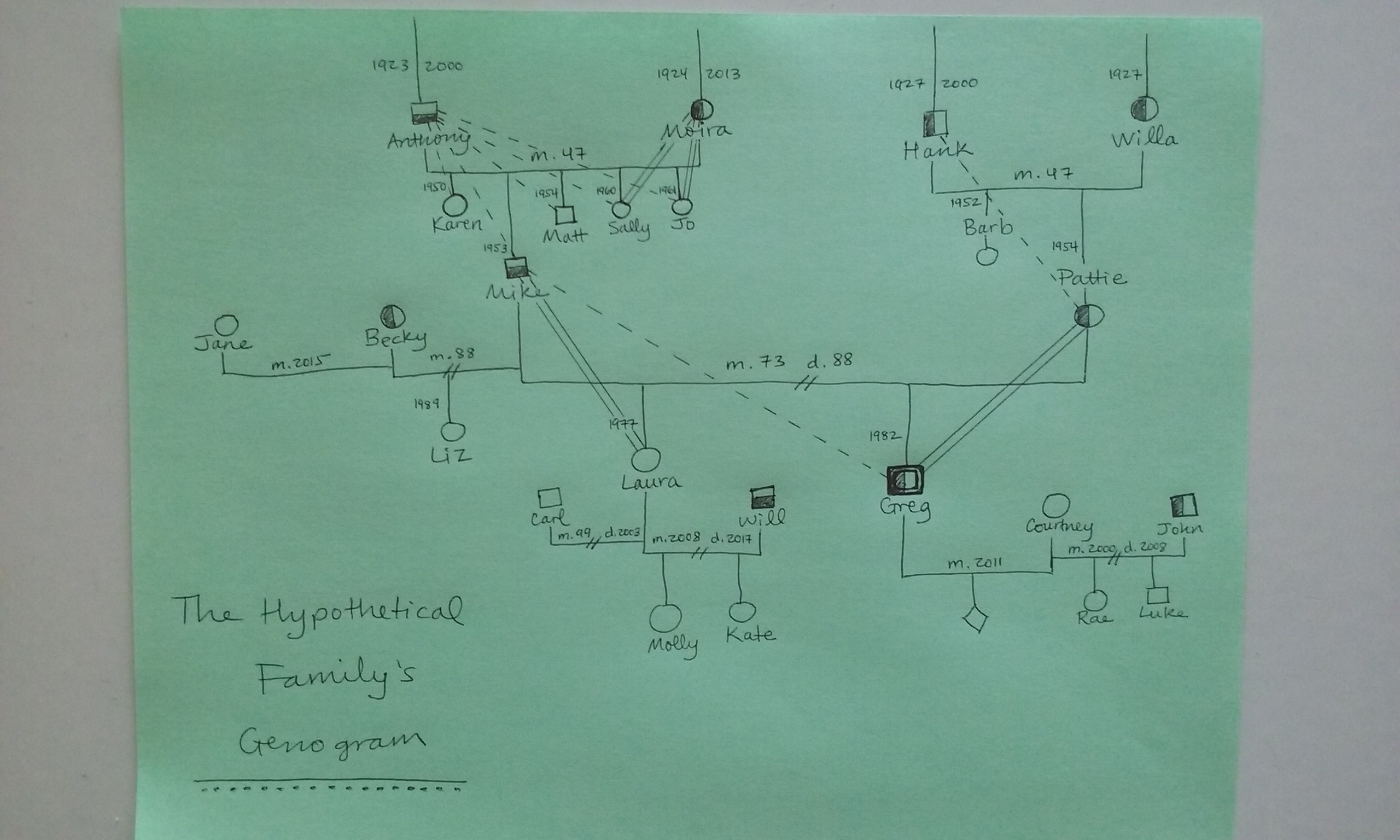

When building a client’s genogram, I always start with when they were born. I represent them on the page with their name and a shape to designate their gender. Squares are for males, circles are for females, and a combination of one inside the other is for transgender individuals. I outline this shape again to denote that they are the index person around whom the genogram will grow. (Note in the hypothetical example above that Greg is this person.)

The next step is to add siblings, assuming there are any. If a sibling is older, they are placed to the left of the index person; if younger, to the right. This structure changes to accommodate multiple marriages. (See how Greg’s father remarried and had Greg’s younger half-sister with his second wife, Becky.)

In many cases, people need an entire session to start exploring the relational dynamics that existed and might still exist amongst them and their siblings. We typically take for granted that our parents have the most significant effect on our development. Genograms can help underscore the impact that siblings have, as well.

Birth Order

In exploring sibling relationships, I like to provide clients with some psychoeducation on birth order. There are well-tested theories that make strong connections between personality and whether someone is a first-born, middle-born, or last-born child.

First-borns, for instance, tend to be perfectionists, leaders, over-achievers. They are conscientious and reliable, often utilize black-and-white thinking, and love to read. Unlike later-borns, these children only have adults to emulate and are therefore resemble “little adults” themselves. They’ve got some big shoes to fill.

Middle-born children take the opposite approach of their older sibling; they do their own thing. These individuals are often the ones who defuse conflict amongst other family members. They are very loyal and place a deep value on friendship, but at the same time they can be secretive. Middle-borns are typically not comfortable with being the center of attention because they never got a lot of practice in that role.

Last-borns, on the other hand, love to have all eyes on them; they tend to be the funny, fun-loving sibling with good people skills. But in some cases, to some degree they’ve also endured bullying at the hands of their older siblings. Perhaps they received the message that they were stupid or inferior, or that their opinion didn’t matter enough. This can be a hard message to shake.

Exceptions

Of course, not everyone fits the mold suggested by their birth order. But usually the reason behind a given discrepancy is relatively predictable. For example, gender can make a big difference. If a last-born individual presents more like a first-born, it might be that he is a first-born son with one older sister. One must also consider the physical and mental health of their family members. If a first-born daughter, for instance, has a major disability, her younger sister will probably display more first-born traits. Another exception occurs when more than five years separates the births of two children. If you were, say, seven when your younger sibling was born, that sibling will likely have some first-born characteristics.

The birth order of one’s parents also plays a part. A middle-born mother is more likely to identify — and therefore favor — her own middle-born daughter than she is likely to identify with her first or last-born children. If both parents are first-borns, they will probably raise three children who all have a noteworthy amount of first-born traits, regardless of their actual birth order.

Talking about all of these nuances and how they apply to a client’s unique sibling constellation can often deepen understanding of and compassion for family members and help illuminate the hidden, pre-programmed motivations behind everyone’s behavior.

Relational Dynamics

Genograms use different kinds of lines to denote different kinds of relationships. For instance, if a client was very close with her older sister, I draw two solid lines connecting their respective shapes on the graphic. If she felt emotionally distant from her younger brother, I draw a dotted line to connect them. Jagged lines represent abusive dynamics between a pair of family members. Two lines with a bracketed gap in the middle denotes that a cut-off happened, or that communication completely stopped for a significant amount of time.

I am never surprised when a client reports a cut-off between two people in one generation of a family and later mentions another cut-off between two people in the previous generation. Such patterns are yet more proof that ways of dealing with pain and conflict tend to be passed down through the years. Mental illness (indicated by shading in one vertical half of a given person’s circle or square) and substance abuse issues (indicated by shading in the lower horizontal half) also tend to reoccur from one generation to the next.

Triangles on the Genogram

Triangles are another element of relationship in a family that genograms can include. One tenet of family systems theory is that a dyad, or a pair of people, is unstable. So when any sort of conflict arises, the dyad will enlist a third person for “support.” The nature of this support varies greatly from family to family.

A common scenario involves the two parents arguing and one of the children stepping in to defend mom or dad. Or a child might develop some sort of issue, like an eating disorder, and become the focus of one parent. (I denote this focus on the genogram by drawing a solid line between the two family members, with an arrow pointing to the child in question.) Meanwhile the other parent feels neglected by his spouse and might then seek emotional support from another child. In this way, an additional triangle forms.

The Drama Triangle

Another typical arrangement is the Drama Triangle. This occurs when one person takes on the role of bully, the other of victim, and the third of hero. Sometimes these triangles can get especially messy. The hero, upon swooping in to save the day, is then cast as the bully, while the original victim becomes the hero and the original bully becomes the victim!

Where Drama Triangles are concerned, a good step toward healthy change is for the person in the original hero role to resist coming to the victim’s rescue in the first place. The victim will then have no choice but to step into his own efficacy. I denote such dynamics on a client’s genogram by shading in a triangular space that connects three family members. Sometimes these shapes overlap, with one family member playing a role in two or more different triangles.

“If it’s heavy, put it down.” -Clem Snide

One other aspect of family systems that genograms help illuminate is how maladaptive beliefs, or “burdens,” are handed down. The genetic foundation of mental illnesses like major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder has received much attention in the world of clinical research. However, there are subtler cognitive behaviors that we all inherit from parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and so on. The creator of internal family systems therapy, Richard Schwartz, uses the term “burdens” to characterize these unhelpful thought patterns.

Body Image

Body image issues comprise a good example of such burdens. Children of mothers who consistently convey dissatisfaction with their bodies will often subconsciously assume that they should feel the same way about their own bodies. Deep down in their basic nature, they might actually like their bodies. But they’ve inherited the burden of a poor body image! The negative self-talk that colors their internal world isn’t actually their own but their mother’s, and perhaps their grandmother’s.

Guilt

Do you find yourself feeling guilty on a regular basis? Think about your family context for a minute and see if you recognize any other relatives with a similar issue. Perhaps your grandmother was frequently guilt-ridden, causing her son (your father) to resist ever feeling guilty because even a little bit of such intense guilt was too much to bear. Later, upon having children of his own, he inadvertently projects his disowned guilt onto them, and the cycle continues.

Without a mindful awareness of how guilt is an inherited burden that spreads a false message, you could never take steps toward changing that painful pattern. Only when something moves into consciousness can we deal with it effectively. Genograms can help us see harmful patterns in stark relief, opening the floor for a conversation about setting our burdens down.

“Taken out of context I must seem so strange.” -Ani Difranco

The various ways to use genograms in the therapy room are too numerous for the confines of this blog post. But the broadest and most important function they serve is to help clients literally see that they are part of a much bigger system than they might have realized. John Donne said, “No man is an island.” Applied to family systems, this statement suggests that everyone is connected to, affected by, and dependent on everyone else.

The nature of our parents’ upbringing has an undeniably huge impact on our own upbringing, which in turn affects how we raise our children. Even if every parental decision is a rebellion against how our parents did things, it is still the result of how our parents did things! Humans are contextual creatures. Therefore, to understand ourselves in a way that promotes healing, we must understand our unique context.

Resources

Galindo, I.; Boomer, E.; and Reagan, D. (2006). A family genogram workbook. Kearney, NE: Morris Publishing.

Leman, K. (2009). The birth order book. New York, NY: MJF Books.

McGoldrick, M.; Gerson, R.; and Petry, S. (2008). Genograms (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Norton Publishing.

Schwartz, Richard (1995). Internal family systems therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.